Editor’s note: This is an excerpt from a special edition of Arches magazine that commemorates the 50th anniversary of the Watson Fellowship, in which we explore the travels, stories, and reflections of Puget Sound’s fellows. For the best viewing experience, download the autumn Arches PDF.

Painting by My Nguyen. Photo: Sy Bean

My parents and I escaped Vietnam when I was 2. For my Watson project, I went back to my homeland, and I met my extended family for the first time. I had heard the names of my grandparents and my uncle and my aunts. But beyond that, I really knew nothing about them.

The minute my husband and I arrived at the airport, there was a little village waiting for us out there. It was almost like they knew me from the few pictures that my parents had sent over the last 21 years. They welcomed us in. We just felt so loved by them.

When I traveled to Vietnam, I thought that I was a very respectful, good Vietnamese daughter. I knew the language enough to get around. I thought that I understood the culture enough, but I didn’t. The less you know, the more you think you know. And the more you see, the more you realize you don’t know anything.

I would get really frustrated over cultural things. For example, as a Vietnamese woman, the expectation was that I would go to the market and wash the herbs for the morning, cut up everything and cook, and then hand wash clothes before I could even think about painting. That was a cultural obligation, which, in retrospect, I’m grateful for. But at the time, I was super annoyed, because I was there with an agenda.

My uncle found a way to connect with me. He would say, “You might not be painting, but think of what you’re experiencing.” He was opening my mind up to the experience. He was so loving and open-minded, and so wise. He had a big influence on how I perceived and approached life.

In my sketchbook, you’ll see a lot of pictures of just day-to-day life, cooking, and fruit. That was my way of sneaking in sketching while I was doing housework. The dirt must have been blessed on my uncle’s property, because every fruit tree that grew there was just amazing, so sweet and so good. He had the most amazing starfruit tree, and I felt like I had to capture that.

My Nguyen ’98

Deputy Director of Interior Design and Operations at Holland America Line in Seattle

Photo: Getty Images

The place that had the biggest impact on me was Anjahamana, one of the first remote villages I visited in Madagascar, where I stayed for three weeks. I was hiking to these little forest segments, where there were lemurs left, but you didn’t know how much longer they would be around. The villagers were clearing hillsides to plant rice, and the forest patches were getting smaller and smaller. I saw homemade lemur traps in the forest, and when I was out with guides, someone offered to sell a lemur to me. I was struck by the urgency of the need for conservation, but also the needs of the people. I was starting to under- stand a different perspective.

In another village, I noticed that some people raised chickens. I thought, Well, why doesn’t everyone eat chickens instead of lemurs? I was told, “Chickens you can sell, and get money to buy other things you need. Lemurs you’re not supposed to sell, so sell the chickens, eat the lemurs.” What I took away is that conservation is complicated. It should be approached with compassion, and a willingness to at least try to understand the perspectives of different stakeholders.

Mary Kotschwar Logan ’03

Stay-at-home mom in Camarillo, Calif.

Photo: Guillaume Briard

In every place I went, I tried to capture my feelings of awe at the landscapes. The tiny hut in the corner of the image, swallowed up by the landscape: I was constantly trying to take those pictures, to somehow capture how small I felt in those places, and the scale of human infrastructure alongside the natural world.

I was looking for how other people see the same landscapes, but have very different thoughts about what to do with them, or what they’re supposed to mean, either personally or to the country. These concepts are all culturally relative, and I think that’s one of my big takeaways from the Watson trip. I have more questions and fewer answers than I started with.

Rachel Gross ’08

Postdoctoral fellow at the University of Montana in Missoula

Photo courtesy of Erich Von Tagen

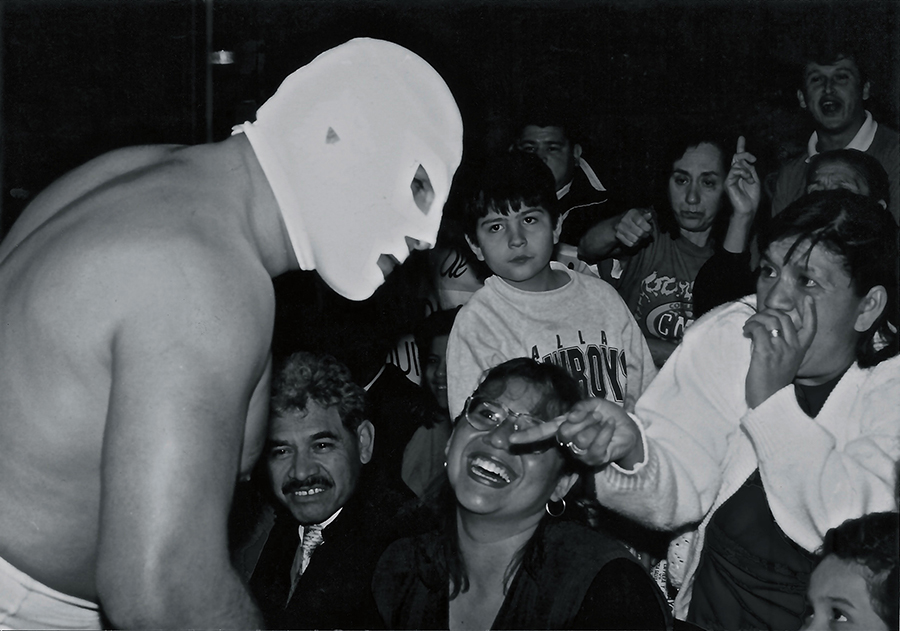

I wanted to be able to express the relevance of lucha libre, to talk about the idea of the sporting spectacle. As an athlete, I found that it was something I could speak to and understand, but I also wanted to step out of that mold and look into what athleticism as performance means culturally.

I was definitely an outsider, but I was seeing lucha libre in Mexico City, in the Arena Coliseo and the neighborhood with the crowds that were there every Saturday. People love it. It doesn’t matter who you are—young or old, man or woman, rich or poor—it’s a universal thing. You go to these shows and you see all sorts of people. It was beautiful to see the interaction of the performers with the audience, because for both it was a moment of truth—they were able to be themselves during that space and time.

You can’t really imagine this great feeling—there’s a glow to it. Pro wrestling was real to people, and they loved it.

Erich Von Tagen ’97

Film and television production coordinator in Portland, Ore.

Photo: Tom Gildon

I studied comparative sociology and anthropology, and I was able to apply the participant-observation method to contortion and acrobatics for my Watson project. I was able to participate in the training methods and also to look at the culture of the people around me and how their arts and training interacted with culture.

I hold Mongolia very dear to my heart. I did a homestay with a nomadic family who lived out on the steppe with this huge blue sky and rolling hills. We milked the goats in the morning.

I loved training in this one particular studio where students were training intensively six hours a day, practicing really challenging and, at times, painful skills, and yet there seemed to be so much pure enjoyment and delight in the process. It challenged my stereotype of the intense Asian acrobatic culture to realize that these students wanted to be there, and they appeared to be enjoying it, hand in hand with challenging themselves and pushing their boundaries.

Jacki Ward Kehrwald ’10

Communications and events manager at The Circus Project in Portland, Ore.

Photo courtesy of Margaret Shelton Betts

I had been studying harp for about five months, and I was sort of harped out. I needed to take a break. I decided to go to Lisieux, a little village in France, to learn about Thérèse of Lisieux, who is one of my favorite saints. Her parents, Zélie and Louis, were the first saints to be canonized as a married couple. While I was there I stayed in a convent—I had been considering becoming a nun since I was a child.

It turned out that St. Thérèse loved the harp, and actually drew a little coat of arms for herself with a harp on it. So even when I tried to escape the harp, it came back to me, and I felt like it was a sign that I was on the right road. I realized, I don’t think I’m destined to become a nun. Years later, I got married, and when we had our first daughter, I named her Zélie Thérèse for my unexpected little trip to France.

After I had my daughter, it was a lot harder to be flexible and spontaneous. We bought a fixer-upper that ended up being very difficult, and we had some deaths in our family, and my husband is in the military and was deployed a lot. And I kept feeling like, I’m on the wrong road. How could I discern that same good gut feeling I had when I was traveling? I had to reevaluate what it was that I really wanted, and not be afraid to reroute my life. So we sold our house, and I went back to work part- time after being a stay-at-home mom. And I started playing harp a lot more. I had taken a hiatus after having Zélie. I realized I just had to make those decisions again. I was letting life come at me. You have to learn the lesson over and over.

Margaret Shelton Betts ’11

Harp instructor and performer in Tacoma, Wash.

Photo courtesy of Kelsey Crutchfield-Peters

One of the really nice things about not having a road map was that it allowed me to have really authentic interactions with people. It made me trust people more.

I was visiting a village in Borneo, and I met some indigenous leaders who invited me to a meeting of villages and tribes in the Baram region who were working to protect their lands from logging and palm oil extraction.

They were speaking about how once logging companies came to their villages, their lives went from being really bountiful and happy to being really hard. There was no food in the forest anymore. The animals had gone. The rivers were full of sediments, and there were no fish. Person after person got up and told these stories.

That was the intro to a journey I then took with a group of people from one of the villages. We traveled through the forest to sites where their ancestors, for hundreds and hundreds of years, had used the paths for hunting and to flee into the forest during World War II.

So they took me to this place that was very important to them. We spent the night dancing, they hunted boar, we had a fire, and we slept out in a traditional-style house.There was this moment where the women came together and were singing. I was struck by the fact that people were so happy to just share that experience with me. They took me in and showed me who they were, very authentically, unabashedly, and beautifully. I felt very grateful.

The whole premise of my project was this idea of people and land use. My Watson year was an extraordinary experience of interacting with people in a really loving way, and I think that’s what came out of it, this feeling of respect and love for people who are just trying to live their lives.

Kelsey Crutchfield-Peters ’14

Graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley

Photo: Alamy Photo

Coming across the grass-lands in Northern Australia and seeing this flock of budgerigar parakeets, which was, like, a kilometer wide and five kilometers long, and thinking it was part of the rain clouds that I was also seeing that day. That was truly amazing.

In that very same day, a colony of flying foxes was taking off and leaving for about an hour, and they were blotting out the sky while they were doing it. There were just thousands and thousands of them. Then, on Nigaloo Reef, which is on the West Coast of Australia and is the longest fringing reef in the world, I got to swim with a whale shark. That was quite an amazing experience, swimming with an animal that could easily fit you inside its mouth, if it wasn’t eating plankton.

Watching the corals spawn on the Great Barrier Reef is truly awe-inspiring, to see the corals send off their egg and sperm bundles. It’s like watching fireworks.

Bryce Maxell ’94

Program coordinator at Montana Natural Heritage Program in Helena, Mont.

Photo courtesy of Mary Walker Curry

Every single person finishing college should have this opportunity, because it sets you up for life, in terms of learning how to jump into an unknown situation and figure your way through.

I had this system I developed. It was my three-day rule. Every time I would get to a new country, I would feel really overwhelmed by the new language, the new currency, the transportation system. And so I’d tell myself, “After three days, you’re going to feel so much better here. Everything is going to be OK.” And it was so true, every single time.

I have applied that to the rest of my life. I work in travel, so in terms of logistics, there’s a direct correlation. But even when I was going through a very tough time as a stay-at-home mom going through a divorce, needing to find a job, and renovating my house all at the same time, I tried to say the same thing to myself. You know, “Everything is going to be OK, and you’ll find the way like you did when you were traveling.” So that was really a great template for life, to have the confidence that it will be OK in the end.Therefore, I’m not afraid.

Mary Walker Curry ’97, M.O.T.’00

Voyage product director/trip planner at Adventure Life in Missoula, Mont. (Pictured on the right.)

Photo courtesy of Jennifer Tillett

Being a Watson Fellow improves you as a human being. I never gave up and went home because it got too hard, because there was always a way. Now, with harder problems, more constraints, deadlines, and lots of difficulties, I still have that playful, creative problem-solving ability that says, Well, what if you just try this? Or, What if we change the goal? Being brave enough to do that and not give up in the face of adversity is really valuable.

Jennifer Tillett ’02

Software engineer in Vancouver, Canada

Photo courtesy of Lisa Tucker

I think that Puget Sound gave me a leg up on the Watson year, because I had tools to process experiences and emotions. I was in the leadership engagement and development cohort, and I was also involved in Orientation for all four years of college. We did a lot of reflection on how we impact communities in the world. I think I was more readily able to enter spaces around the world and to try to understand how I fit into those communities before starting to execute my project. There was an emphasis on introspection and intersectionality. The Watson really fosters those qualities, as well, because it’s what happens when you’re traveling by yourself for a year. You learn more about yourself and how you fit into the greater picture of the world.

Lisa Tucker ’15

Donor advocacy and events associate at the League of Conservation Voters in Washington, D.C.

Photo courtesy of Kendra Loebs

I landed back in the United States right in the middle of the recession. I had just had this incredible experience traveling around the world, but I found that many people didn’t understand or value that experience. Especially when I would visit my hometown in rural Minnesota—people thought I had gone abroad to do missionary work, to hand out bibles or do humanitarian work. They would ask me things like, “Didn’t you find that people are really backwards there?” I’d think about how I had found this incredible humanity everywhere—even if they had totally different cultures or customs, they were just people, and good people. That someone would call another culture “backwards,” when we have so many problems in our own nation, is really just saying something.

Kendra Loebs ’06

Intensive care nurse in Seattle