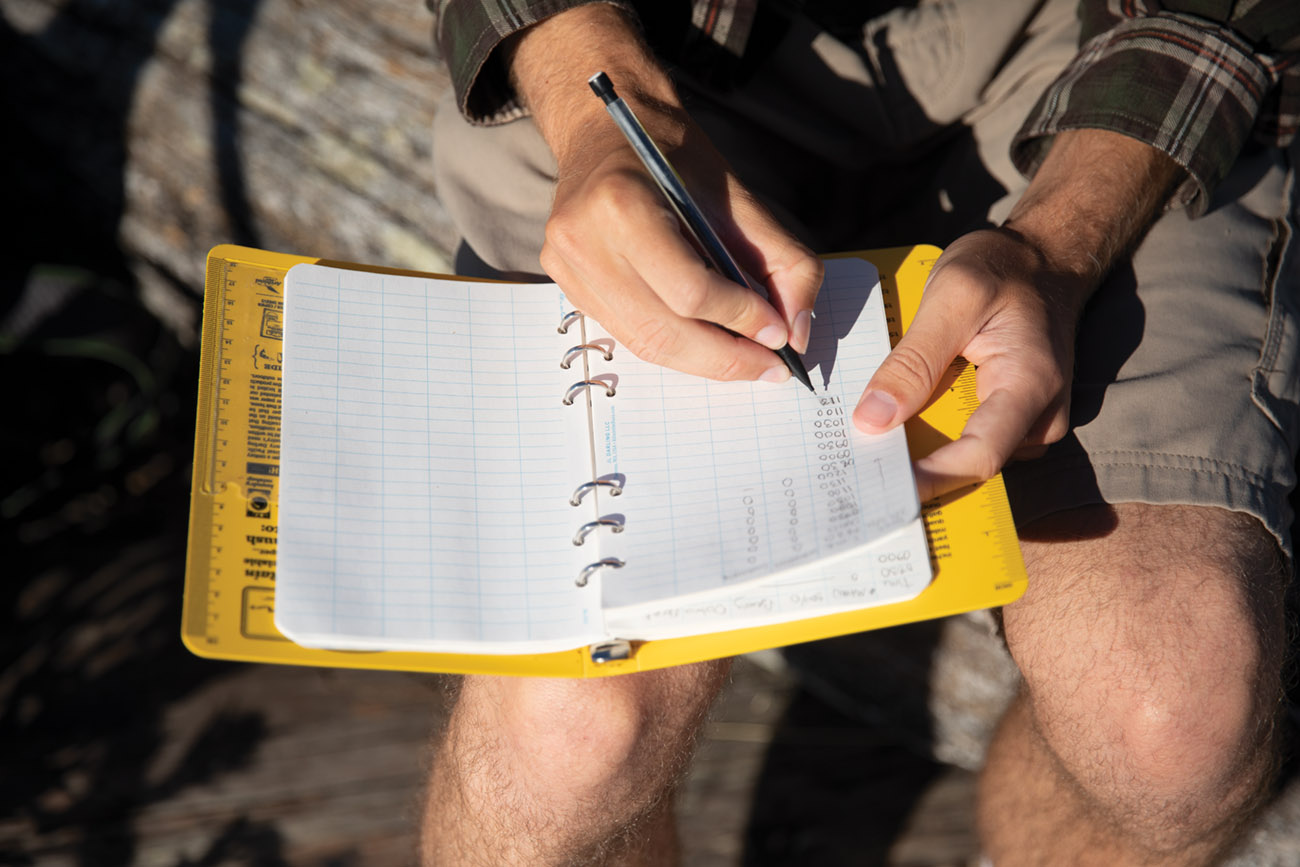

For some of Jeff Tepper’s geology students, the lakes around Puget Sound offer fertile ground for summer research.

On a Tuesday morning in mid-July, Nancy Hollis ’22 was sitting on the deck of a 20-foot pontoon boat on Spanaway Lake, a cashew-shaped body of water in the middle of a residential neighborhood south of downtown Tacoma. Some half a million people visit the lake each year to swim, fish, paddle, and motorboat. But Hollis wasn’t there to play.

Off the edge of the deck, she was lowering a cylindrical device—a bit longer than a rolling pin—via a long cable. The boat was owned by shoreside resident and lake advocate Sandy Williamson, who stood at the helm as Hollis captured water-quality information, such as temperature and pH, at different depths. The information provided a snapshot of the lake’s conditions on that July day. But the impact of those data could be much larger.

Spanaway Lake, like many bodies of water worldwide, is experiencing an explosion of toxic algae—what scientists call hazardous algal blooms, or HABs. A warming climate and an influx of nutrients from sewage, fertilizers, and other human-generated sources trigger the blooms, which kill fish, birds, dogs, and even people, and regularly close recreation spots like Spanaway. Williamson, a retired hydrologist and chair of Friends of Spanaway Lake, has lived on the lake for 16 years; in that time, he’s seen a dramatic increase in the number of HABs, “with no end in sight,” he says.