It’s a murder mystery, and University of Puget Sound students are on the case.

It wasn't a fictional plot twist but a real-life 19th-century cold case that had Mia Steiner ’27 and her classmates huddled around a whiteboard, mapping out suspects and motives. The students were investigating the infamous 1880 Donnelly family murders — an unsolved case that took place in Canada more than a century ago. Their work was part of a Puget Sound class, Murder and Mayhem Under the Microscope, taught by Amy Fisher, professor of Science, Technology, Health, and Society.

A self-proclaimed true crime fan, Steiner said she enrolled in the class as a way to complement her English major as well as learn more about the scientific and historical side of true and fictional crime.

“Since I’m also taking a detective fiction English class, I thought it would be fun to combine them,” she said. “My group had a whole whiteboard with what we thought happened and who did it. It was really fun to work together, explore the archives, and theorize.”

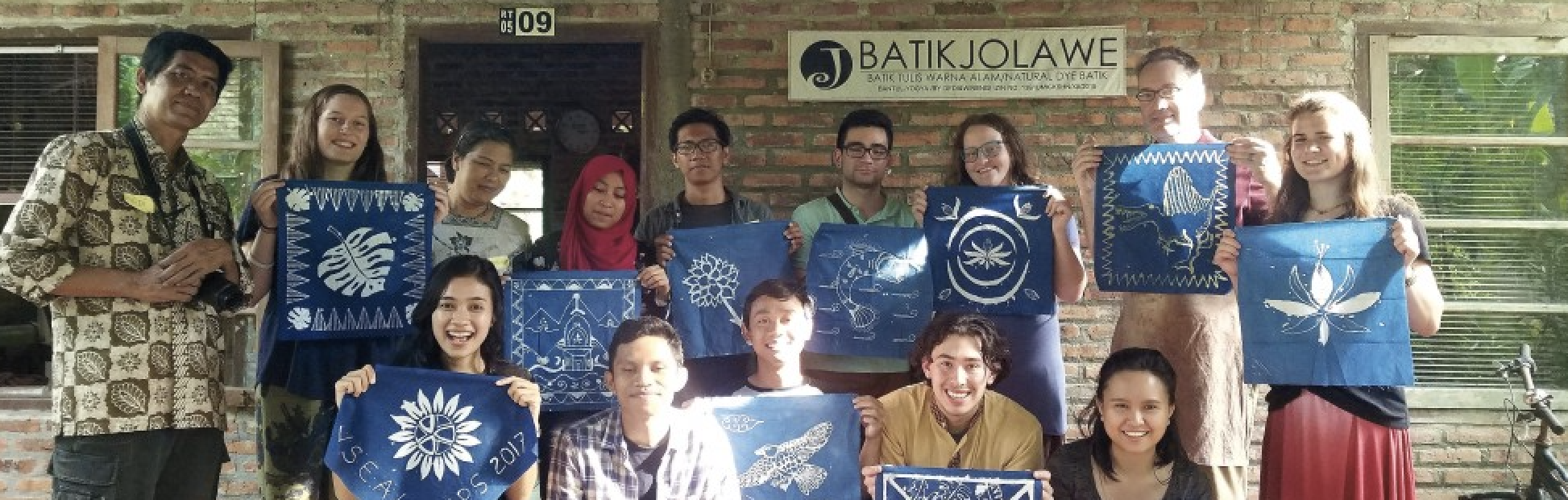

Through engaging activities and research projects, students find a way to see how their own discipline falls within the bigger umbrella of this STHS course, a hallmark of the interdisciplinary learning students receive with a Puget Sound education.

“For example, an economics major studied how business accountants helped unravel white-collar crimes like the Wells Fargo fraud,” Fisher said. “An art history major looked into art forgery for their project. It allows them to see how different disciplines interact and work together around a common area of interest.”

Steiner recalled learning about Eugène François Vidocq, a French criminal-turned-crime-fighter who inspired Edgar Allan Poe’s detective C. Auguste Dupin.

“It was cool to see the overlap with that and getting to see the historical aspect behind it,” she said.

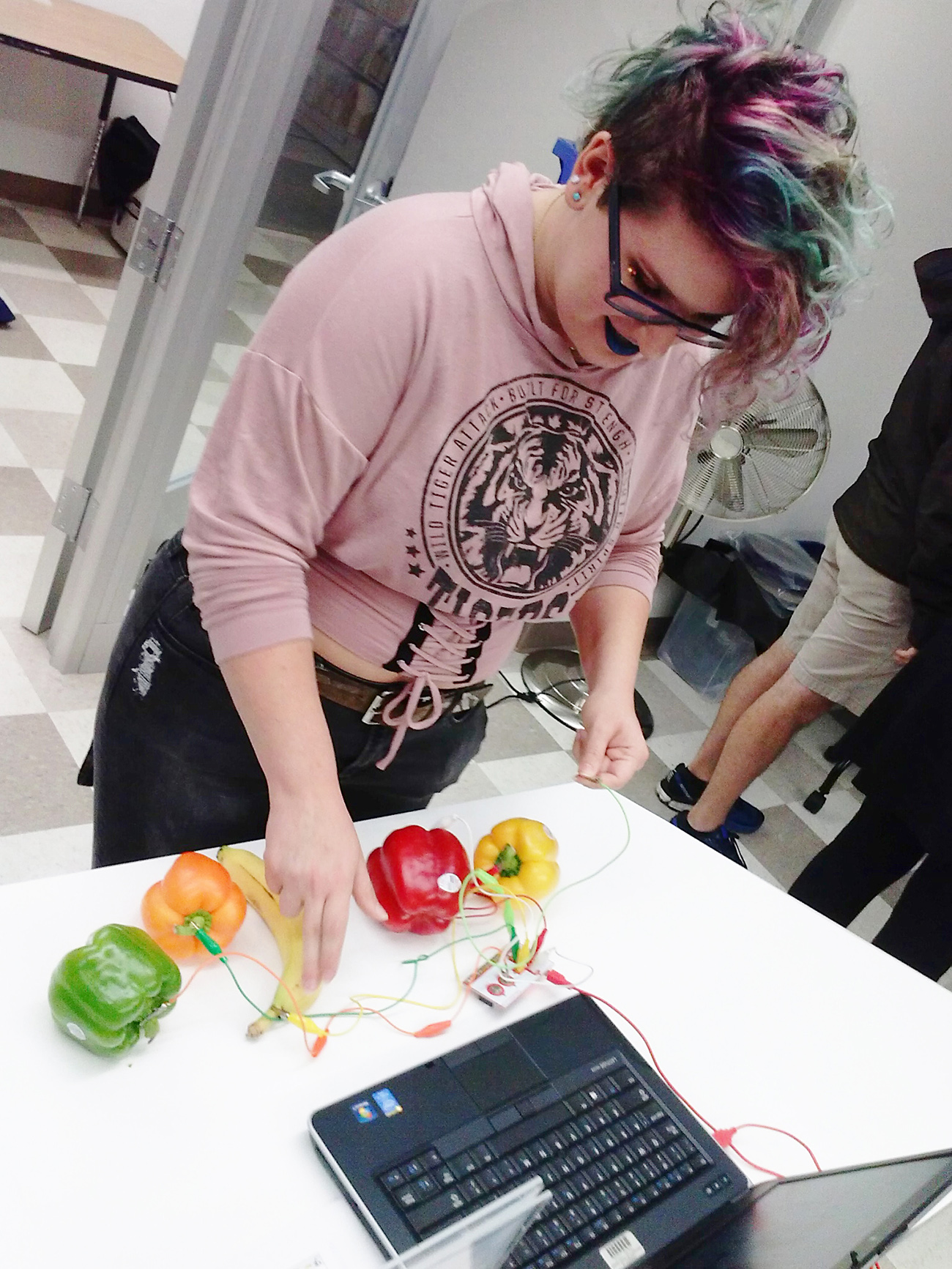

The class provides a unique look at how science and law have intersected throughout history, using engaging activities to illustrate complex topics. History major Jessica Hendrickx ’27 praised the course for its interactivity.

“My favorite parts were the hands-on activities,” Hendrickx said. “There’s this test where you have to smell baby food and try and determine what the flavor is. So we learned there were smell detectives to determine if something was poisoned or not. There’s just a bunch of cool stuff like that, and it makes it fun to be interactive and also work more with your classmates.”

She added that the class appeals to a wide range of students.

“I was really interested starting the first week when we learned about arsenic poisoning,” Hendrickx said. “I would say take it, even if you’re not an STHS major — it’s so much fun.”

With the growing popularity of true crime media, Fisher said one of her key lessons is to remember that real people are affected by these crimes.

“Even white-collar crimes are not victimless,” she said. “The other thing is to understand how messy it is. Crime scene investigation is complicated, and there's often a lot of uncertainty in the actual science. I hope students leave with a deeper perspective on the relationship between science and criminal law and limits of forensic science techniques, some of which have recently started to be questioned, like bite mark analysis and fingerprint analysis.”

Fisher is now preparing to launch her new course, Whodunit?, in the spring semester as part of a three-year grant from The Mellon Foundation to fund the university’s groundbreaking project, “Reimagining Justice and Carceral Systems through the Humanities.” This class will dive even deeper into detective work, focusing on the evolution of policing, interrogation techniques, and the judicial process.

This ongoing research has led to further opportunities for Fisher, who was recently awarded a John Lantz Senior Fellowship for Research for 2026-27. Her fellowship project, titled “Getting Away with Murder? Science and Criminal Law in America and Britain (1850-1930),” will examine debates in medical jurisprudence, focusing on how developments in forensic chemistry and medicine have shaped the rule of corpus delicti — the requirement for sufficient evidence that a crime has actually occurred before a person can be convicted.

For students considering their future, the class offers more than academic curiosity. Hendrickx, who plans to become a teacher, is already using what she learned in her thesis on the Great Plague of 1665. Like Hendrickx, Steiner found some unexpected connections between the class and her own academic interests.

“It’s been a very enjoyable class,” Steiner said. “It’s my first one in the morning on Tuesdays and Thursdays, and it’s always a great way to start the day.”