Summer research students Anna Brown ’26 and Cas Unruh ’28 explore true crime in the media and the technology that’s solving these cold cases

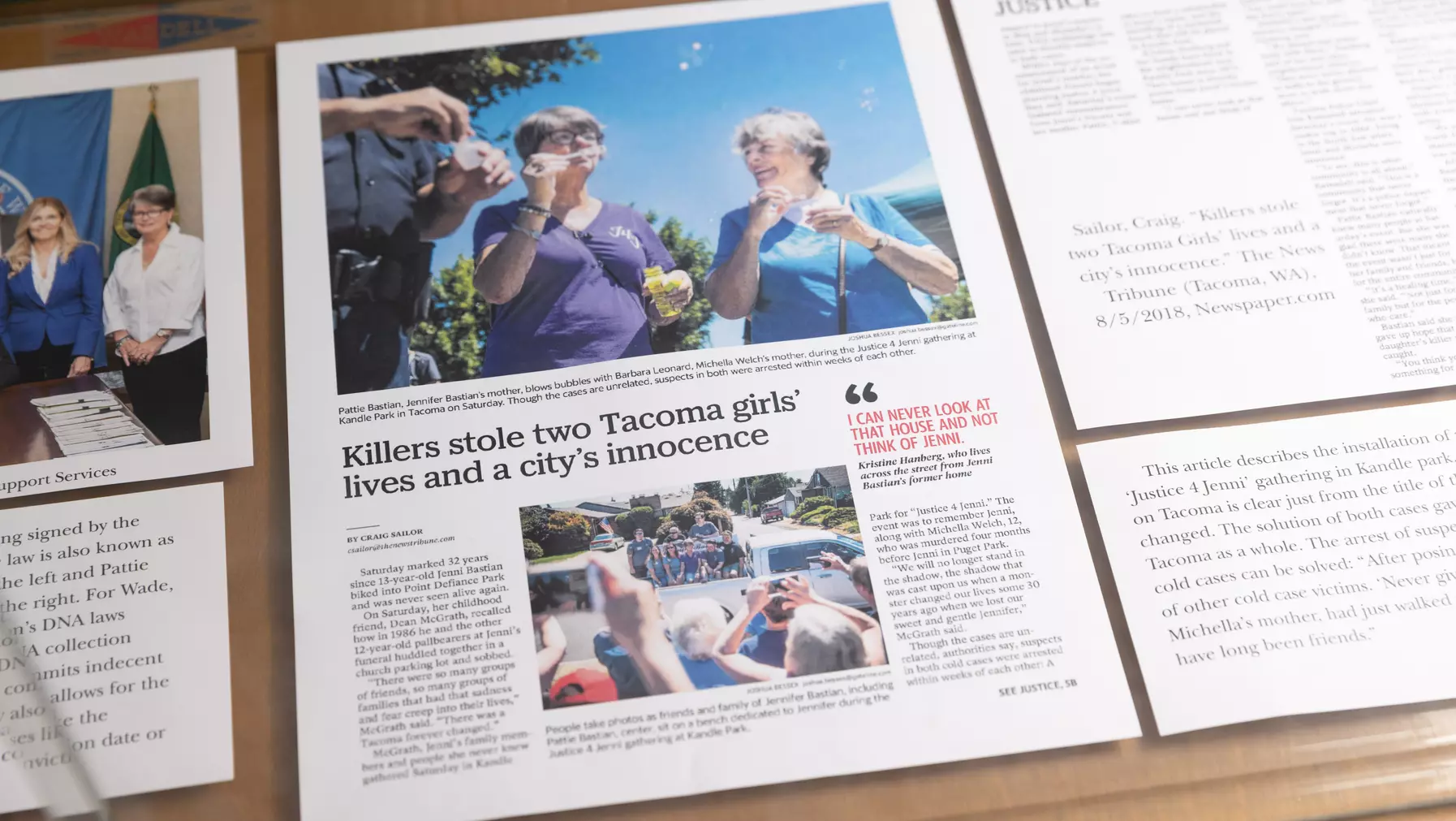

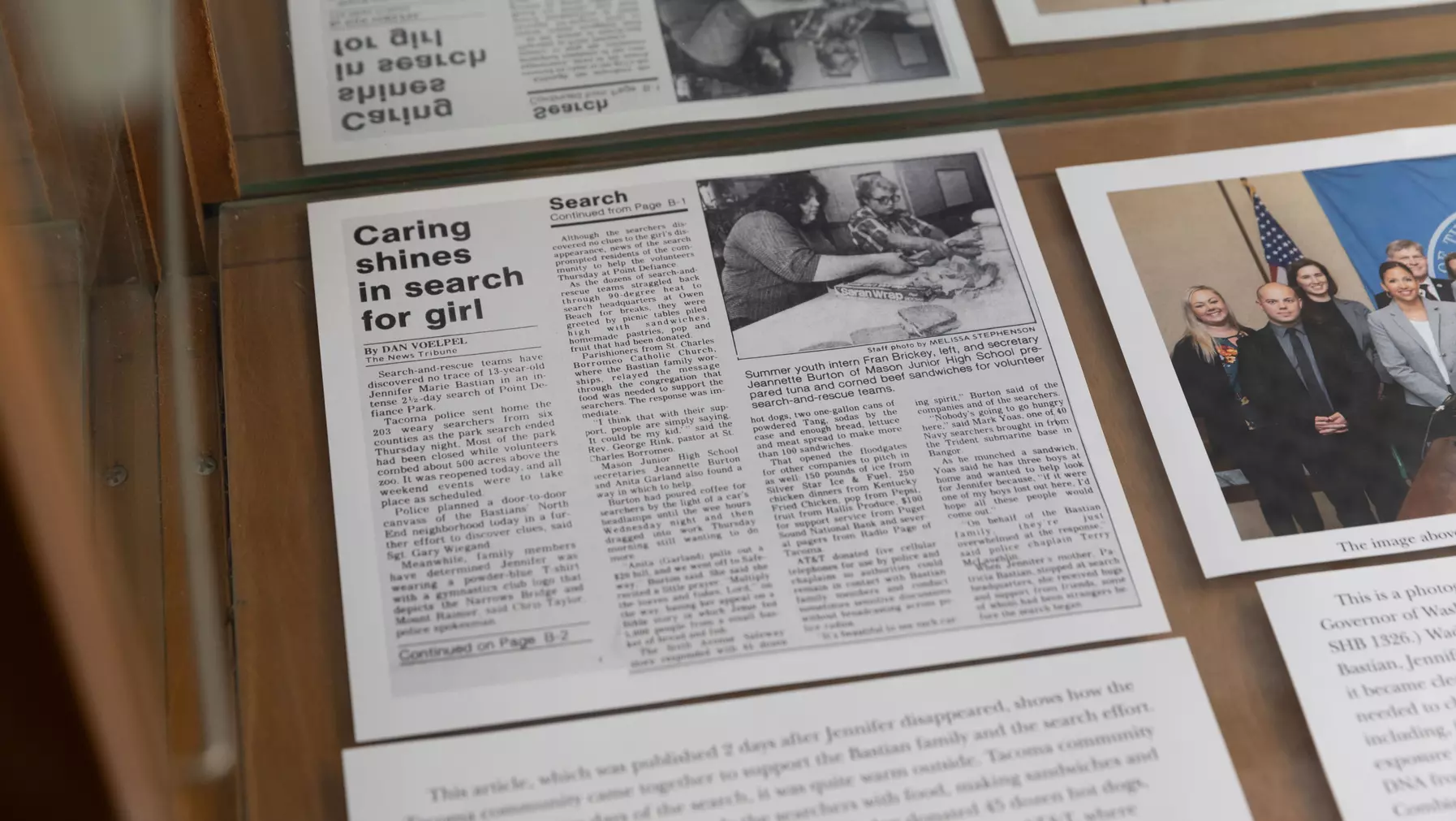

In the spring and summer of 1986, Tacoma was rocked by the shocking rape and murder of two young girls, Michella Welch and Jennifer Bastian. Despite the killings occurring five months apart, the similarities between the victims, including their age, appearance, and the circumstances surrounding their disappearances, were hard to ignore. Locals worried that a serial killer might be lurking in Tacoma’s North End. Despite pressure from the community to bring the killer to justice and continued efforts by the Tacoma Police Department, there simply wasn’t enough evidence to build a case. The trail went cold and both murders remained unsolved for more than 30 years.

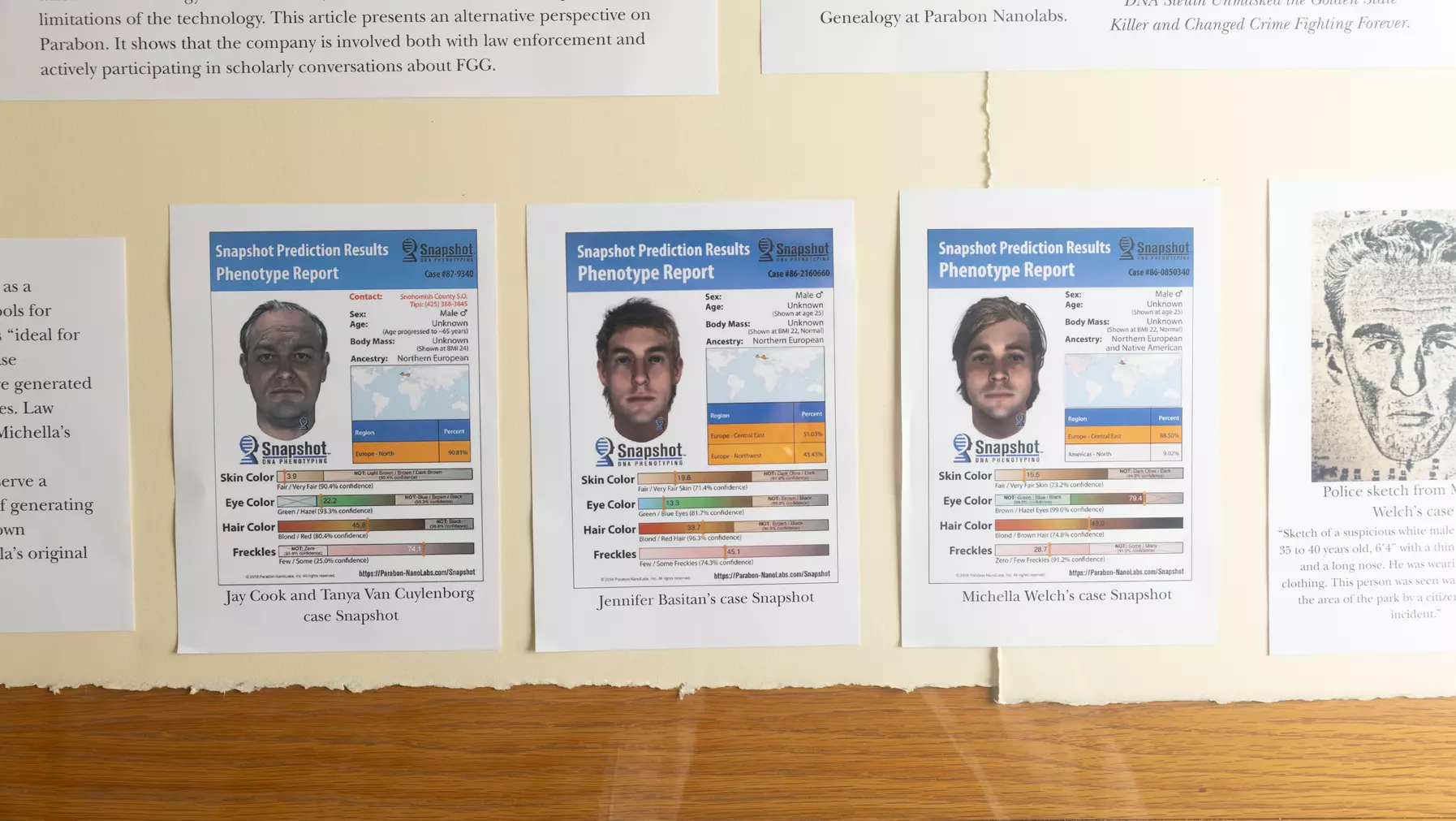

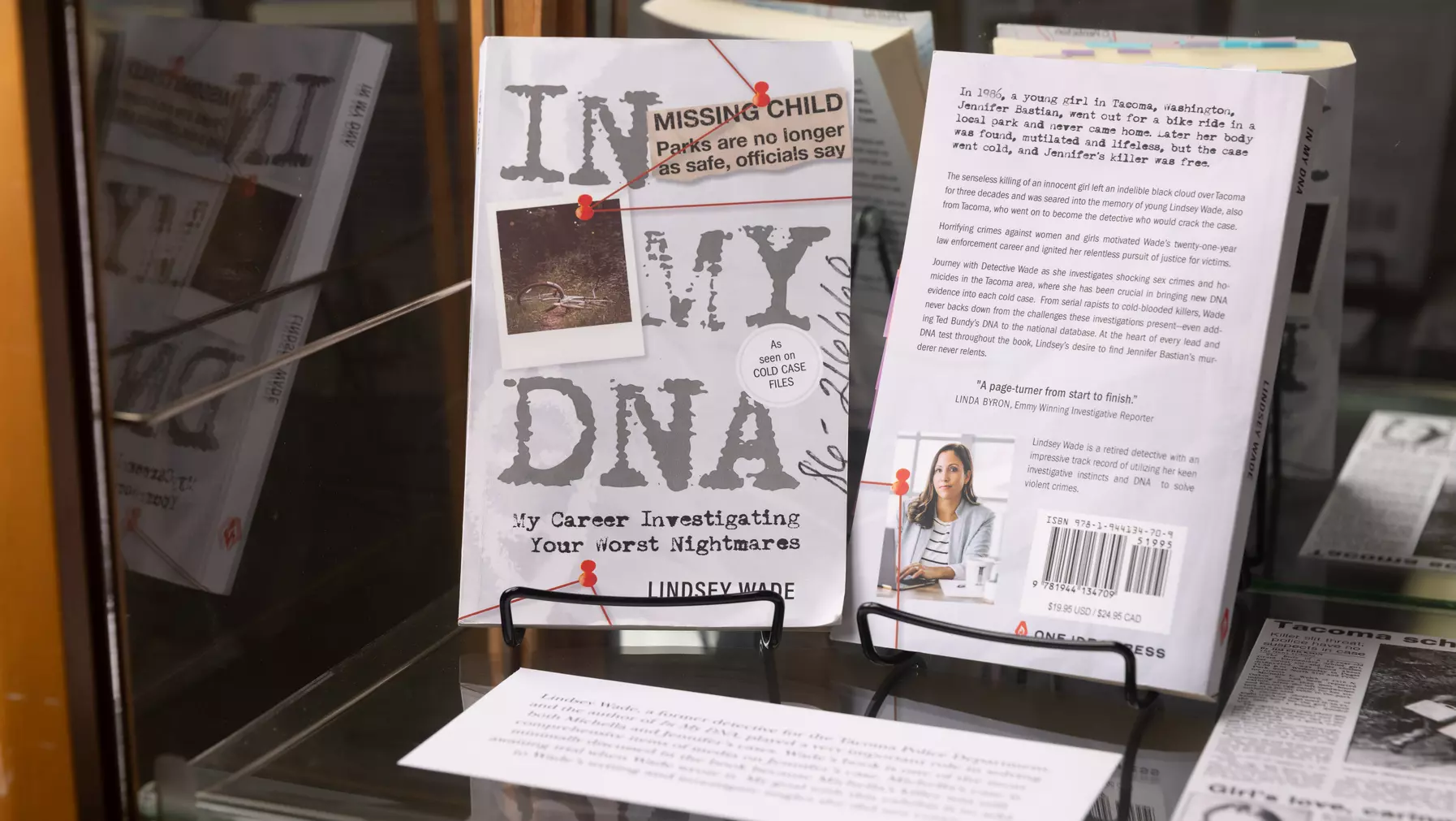

The cases are at the heart of Anna Brown’s summer research project, analyzing these famous cold cases and how new technology helped put the perpetrators behind bars. Brown ’26 is a senior at the University of Puget Sound, majoring in science, technology, health, and society and chemistry. As technology provides the tools to solve many of these previously unsolved murders, including many in Western Washington, Brown was interested in understanding not only how investigators are adopting new methods, but also how solving these murders impacts the victim’s community.

“I've been really interested in true crime for quite a while. So, when I was talking to Professor Amy Fisher about summer research, it seemed like an amazing opportunity to be able to research something that I had been interested in for so long,” Brown said.