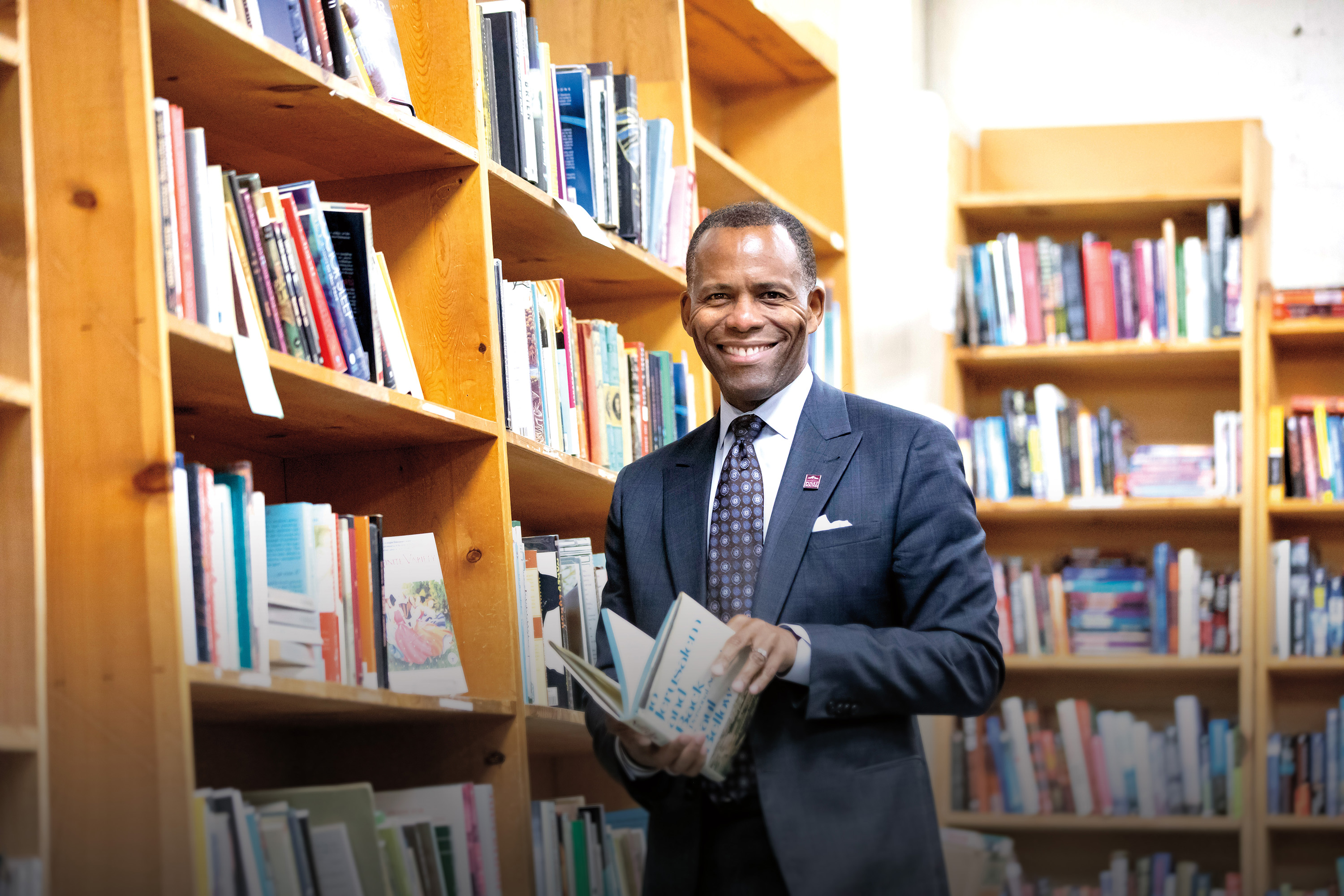

Over the past few months, I have enjoyed meeting with people on campus and in my travels across the United States, and many of them have commented on the President’s Book Club in Arches. It seems our little idea has caught on. Greetings, fellow book lover, and welcome to our next meeting!

This issue’s book continues the theme of looking forward to important trends in higher education and how we are responding to a changing world as a community of scholars, researchers, artists, and teachers. Of particular interest to me, The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge looks forward by looking back— to the very ideals on which the concept of a liberal arts education is founded.

In 2017, the Princeton Press reissued in book form a 1939 essay by Abraham Flexner, founding director of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, who is credited with (among other noteworthy achievements) bringing Albert Einstein to the United States. The institute is a leader for research in the sciences and humanities, and Flexner’s essay stands today as one of the most convincing and compelling arguments for the pursuit of intellectual inquiry as a means of satisfying our innate curiosity about the world. As Flexner writes, “The pursuit of these useless satisfactions proves unexpectedly the source from which undreamed-of utility is derived.”

We see this all the time at Puget Sound. An exceptionally entrepreneurial lot, Loggers are constantly making new discoveries, exploring new ideas, and bringing new solutions to life. You read many of these stories in Arches. The throughline in these stories is clear: A student develops a passion for a particular line of inquiry, approaches it through an interdisciplinary lens, discovers connections among disparate disciplines that produce new knowledge, and ultimately pursues a path after college that is a unique expression of their intellect, talents, skills,

and experiences. Our world needs people who can think beyond the constraints of the times in which we are living in order to create and serve a better, brighter future.

Flexner wonders “whether our conception of what is useful may not have become too narrow to be adequate to the roaming and capricious possibilities of the human spirit.” There is without doubt a thin line separating the useless from the useful. We don’t always know in the moment which is which. Flexner argues that “institutions of learning should be devoted to the cultivation of curiosity,” and not be “deflected by considerations of immediate application.” This is, in fact, how many of the world’s greatest discoveries came into being.

There is much to appreciate about this compact book, which includes a companion essay by the institute’s current director, Robbert Dijkgraaf. Even the most leisurely and studious reader can consume both essays with a relatively small investment of time. I’ve always admired those who can say more with less, and both authors do an exceptionally brilliant job of this.

While it is true that both my office and nightstand are overflowing with publications related to higher education and the pursuit of knowledge, I want to assure my fellow book club members that lurking within the tower of reading material are several titles written in the current century: The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates, Tough Love: My Story of the Things Worth Fighting For by Susan Rice, and even Me by Elton John. You never know where inspiration may lie. If you have a favorite book that speaks to the issues of our time and inspires you to make the most of your education, I’d love to hear about it. Send your book recommendations to me at arches@pugetsound.edu.