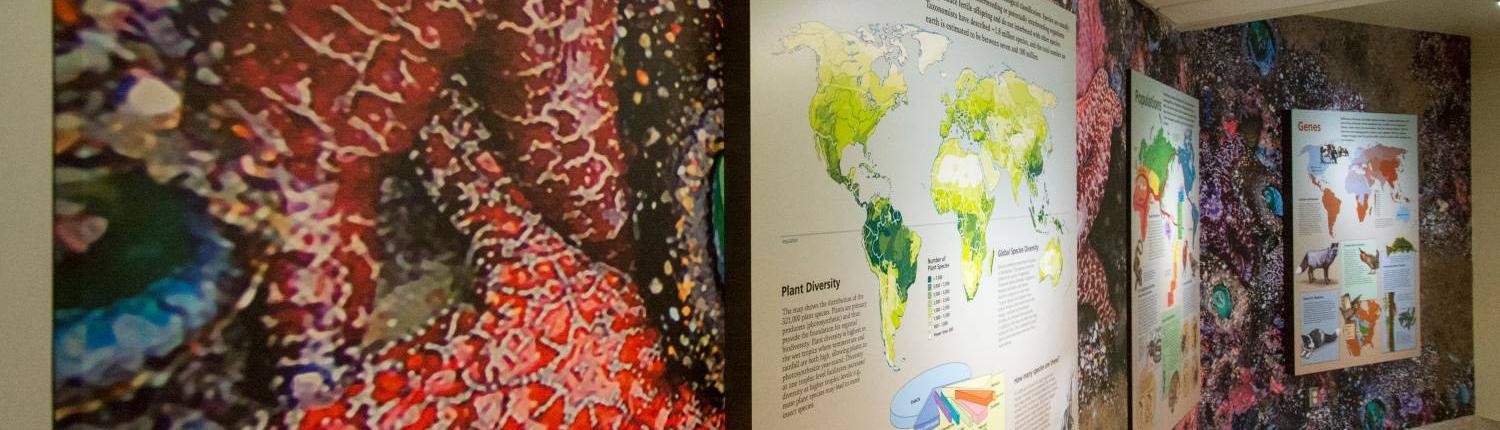

Aggregating Anemone (Anthopleura elegantissima)

This species is abundant along rocky Pacific coasts. Each animal is about 2-3 centimeters wide, but they grow in masses, as the name implies, that may be up to many centimeters in diameter.

KINGDOM Animalia - PHYLUM Cnidaria - CLASS Anthozoa - ORDER Actiniaria - FAMILY Actiniidae

The body of the anemone is firmly attached to a rock substrate, and because of tubercles all over it, detritus and sand adheres to the column, and the animals become almost buried. But when under water, they extend up to 4-5 cm, spreading their tentacles above the sand. They are beautiful animals, with pink-tipped tentacles. Elegantissima means most elegant.

Anemones for the most part are sessile, meaning attached to a substrate. This furnishes both constraints and opportunities. The biggest constraint is that they are not going anywhere; in other words, they have given up the ability to move toward better conditions (e.g., more food) or away from worse conditions (e.g., avoiding predators or adverse physical conditions). In addition, they cannot go looking for a mate. But of course there would have been no evolution of the sessile lifestyle if these constraints could not have been overcome.

Aggregating anemones do not need to find food; it comes to them constantly, as the current carries tiny crustaceans and other animals past their tentacles. All they have to do is capture prey by stinging it with the nematocysts (also called cnidocytes) on the surface of their tentacles. These tiny but complex cells, when stimulated, evert their contents and throw out a barb armed with toxins to immobilize the prey. Many anemones also have nematocysts that adhere to their prey rather than stinging it. The nematocysts also serve as anti-predator adaptations, although not against all predators. Certain nudibranchs prey on anemones, and some of them secrete a mucus that inhibits the discharge of anemone nematocysts.

This and some other anemones are tinged green because of commensal algae called zoochlorellae that grow within them. These algae photosynthesize, and some of the organic compounds they produce are transferred to the host anemone, providing some of its nutrition. This anemone functions something like a plant in the intertidal zone!

The species reproduces asexually by budding off small individuals, which then grow to maturity. When you see a mass of these anemones, they are a clone, all individuals genetically alike because of this. But when two of these colonies develop next to one another, they engage in what could be called “clone wars.” They have special tentacles around the rim, and those on the edge of the colony deploy them against the adjacent colony and force it back, so there is always a clear separation between the colonies.

Anemones also reproduce sexually, and in this species, individuals are either male or female. During the summer breeding season, the mature anemones release gametes (sperm and eggs) into the water, and the fertilized eggs develop into a free-swimming larva called a planula. After further development, the planula sinks to the bottom and attaches as a tiny anemone. Thus both sexual reproduction (mixing of genes) and dispersal are effected