How a failed attempt at major league ball, and an invitation from Puget Sound, launched Casey Sander's acting career

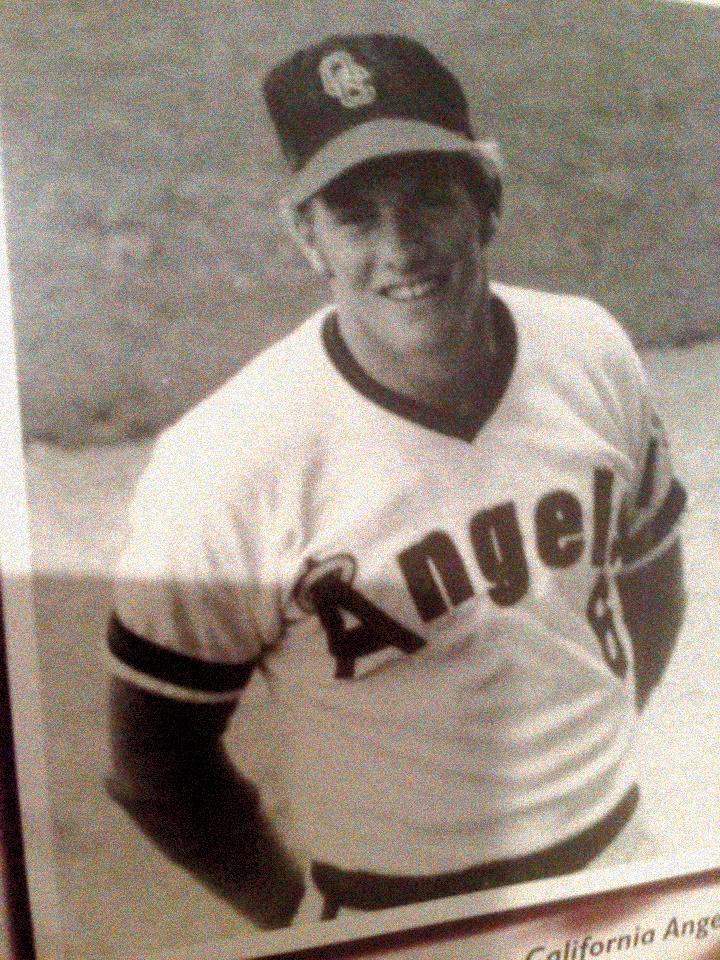

It was 1975, and a 19-year-old kid who had dreamed of just one thing in his short life—to play major league baseball—was, on this April day in Southern California, a mess. A former draft pick of the California Angels, Casey Sander ’79 had been cut just 48 hours earlier by the club after his third professional season. Despondent, he cried in the locker room showers for hours. Clearly, baseball dreams die hard.

But then, in the equivalent of a madcap dash from first to home, Sander drove all night from the Angels’ training site in El Centro, Calif., to Arizona, hoping for one last shot. He went to four different cities in one day, offering his outfielder/first baseman services to four other teams as they were wrapping up spring training.

Nobody wanted him.

Out of options, he took to the long, lonely road leading home to Seattle. A California Highway Patrol officer stopped Sander going 95 mph on Interstate 5 through Burbank. The driver’s eyes were puffy from crying. The officer glimpsed an Angels gear bag on the rear seat of Sander’s 1972 Datsun 240Z.

“He said, ‘You play for the Angels?’” Sander recalls. “I said, ‘Not anymore. I was cut.’” The officer couldn’t bring himself to write a ticket. “His exact words were: ‘You’ve got enough bad news for one day.’”

Little did he know then, but Sander would be back in Burbank more than 15 years later. This time as a TV star.

His is a Hollywood tale, the story of spit-and-leather aspirations dashed by a series of injuries. It’s the story of unexpected second chances, with a beloved University of Puget Sound coach offering new beginnings. And, ultimately, it’s the story of transformation, of a man who found an acting career by happenstance, and who, as an artist, has been driven for four decades to put “skin on words” as he brings characters to life.

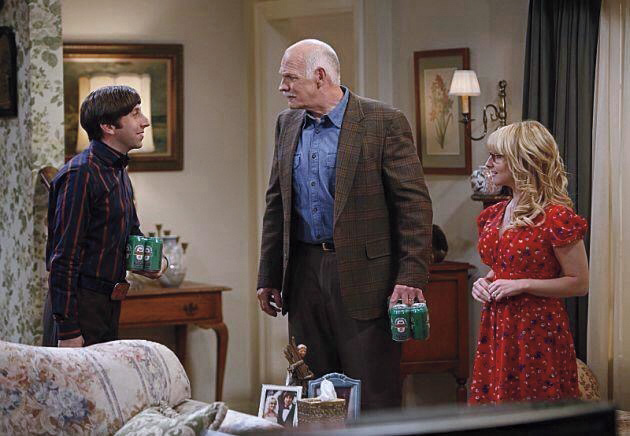

Viewers will know Sander best from his recurring roles on Home Improvement (in which he played Rock Lannigan, a classic American working man), Grace Under Fire (as Wade Swoboda, proud Vietnam veteran and doting husband), and The Big Bang Theory (ex-cop Mike Rostenkowski, loving father to Bernadette and ambivalent father-in-law to Howard). Each show rose to No. 1 in the Nielsen ratings. (“How many people can say that?” Sander muses.) The Big Bang Theory and Home Improvement took Sander back to Burbank, where both sitcoms were filmed. In his career, he counts more than 300 television and movie credits.

The story starts more than 1,100 miles north of Tinseltown, in north Seattle’s View Ridge neighborhood, where Sander played Little League catcher and gained a reputation as a spray hitter who also could punch a baseball into the gap. But it was his speed and dexterity on the high school football field, where he played running back, that brought offers of scholarships from Puget Sound and all four Washington and Oregon schools represented in the Pac-8.

Sander turned them all down, banking on being drafted by a Major League Baseball club. Several teams had shown interest, and taking a college football scholarship would have lowered his draft status. “I gambled on myself to make my dream come true,” he says.

He was taken in the 10th round of the 1973 draft by the California Angels. But baseball quickly turned mean on Sander. In his first season in the minor leagues, for a farm team in Idaho Falls, Idaho, a ball skipped off the turf and struck him in the right eye, shattering his orbital bone. (Careful TV viewers will notice a slight droop of his eyelid.) During winter ball the following year, he suffered a fractured vertebra in his lower back. And the next year, at Quad Cities, Iowa, he tore cartilage in his right knee. It was shortly after that that the Angels cut him.

I'm this 6-foot-3, 230-pound running back, and I call my mom to say that I just got cast in a play. She told me that when a door opens, walk through it."

– Casey Sander ’79

Back in Seattle, Sander wasn’t ready to give up baseball. He joined the Seattle Rainiers independent team (no relation to the Tacoma Rainiers, the Triple-A team for the Seattle Mariners). Then came the most unexpected of phone calls: Puget Sound head football coach Paul Wallrof—“Big Wally” to those who loved and played for him during a 19-year career—wanted to chat with him about enrolling at the school and playing Division II football.

Wallrof hadn’t been able to land Sander three years earlier, but he was willing to give the erstwhile prospect another chance after attending a Rainiers game—unbeknownst to Sander—the night before. Say yes, Wallrof told him, and I’ll give you a full athletic scholarship.

“To this man, I owe everything,” a misty-eyed Sander says today. “During the game, I was, like, 0-for-4, with a couple of weak ground balls. He said, ‘I came to see if you could still run, because I need a running back.’ It was like someone threw me a lifeline.”

(Wallrof died Aug. 28, 2018, at his home on Vashon Island, just weeks before a scheduled team reunion to celebrate the coach. He was 86. Sander was a pallbearer.)

Sander enrolled at Puget Sound as a 20-year-old freshman and went on to play four years of football for the Loggers. He sat out most of his freshman year after twice wrecking his left knee, requiring surgery both times. But he regained his form and, during his senior year, he logged more than 200 carries without losing a yard.

Teammate Frank Washburn ’75, now a retired Seattle principal, also was a running back. Sander, he says, was all legs. “Once he got going from behind the line of scrimmage, he was pretty quick,” Washburn adds. “His style was to be elusive. He was a great athlete.”

A communications major at Puget Sound, Sander called basketball games for the campus radio station, an outlet for his natural gregariousness. One of his communications courses required students to audition for a play—to “find out what the nervous audition process is all about,” he says.

He auditioned and, to his surprise, landed the role of Lucky in Samuel Beckett’s absurdist comedy Waiting for Godot.

“I’m this 6-foot-3, 230-pound running back, and I call my mom to say that I just got cast in a play,” Sander says. “She told me that when a door opens, walk through it. You never know what’s on the other side.”

Theater felt much like athletics to Sander. Both require self-motivation, and opening-night jitters proved to be no different from pregame jitters. The camaraderie of the cast had much the same feel as being a member of an athletic team. The successes proved to be equally exhilarating.

Sander went on to perform in the Greek comedy Lysistrata and a number of other campus productions. He loved it. But theater always was more of a hobby than a calling. Sander had plans to teach English, and he did just that, as a student-teacher at Tacoma’s Curtis High School.

He lasted half a year.

Sander was in the lunchroom listening to teachers talk about their plans for Thanksgiving, and he sensed an indifference in his colleagues. “At that moment, not one of them wanted to be there,” Sander recalls. “I’m the typical young teacher, fired up about doing it, and I’m having a great time.

“I’m looking at these guys and thinking, ‘I don’t want to be you. You’re not happy.’”

It was a crystallizing moment. Over dinner with his mother, Sander shared his plans to drive to Los Angeles and try his hand at acting. He wanted to give it a good two years. His mother paused to take a gulp of her MacNaughton and water, leveling a gaze at the youngest of her five children.

“I don’t know why that doesn’t surprise me,” Sander remembers her saying. “You’ve never done anything normal. Nobody goes and plays pro baseball; you went and did it.”

Driving south, Sander diverted to Reno, where he played blackjack in hopes of doubling the $3,000 he had brought to help himself get situated in California—but instead lost half of it. In Los Angeles, he found bartending work and a place to live. He joined a friend as a scene partner for one of her auditions, and an agency approached Sander, not his friend, saying they wanted to represent him in his acting pursuits.

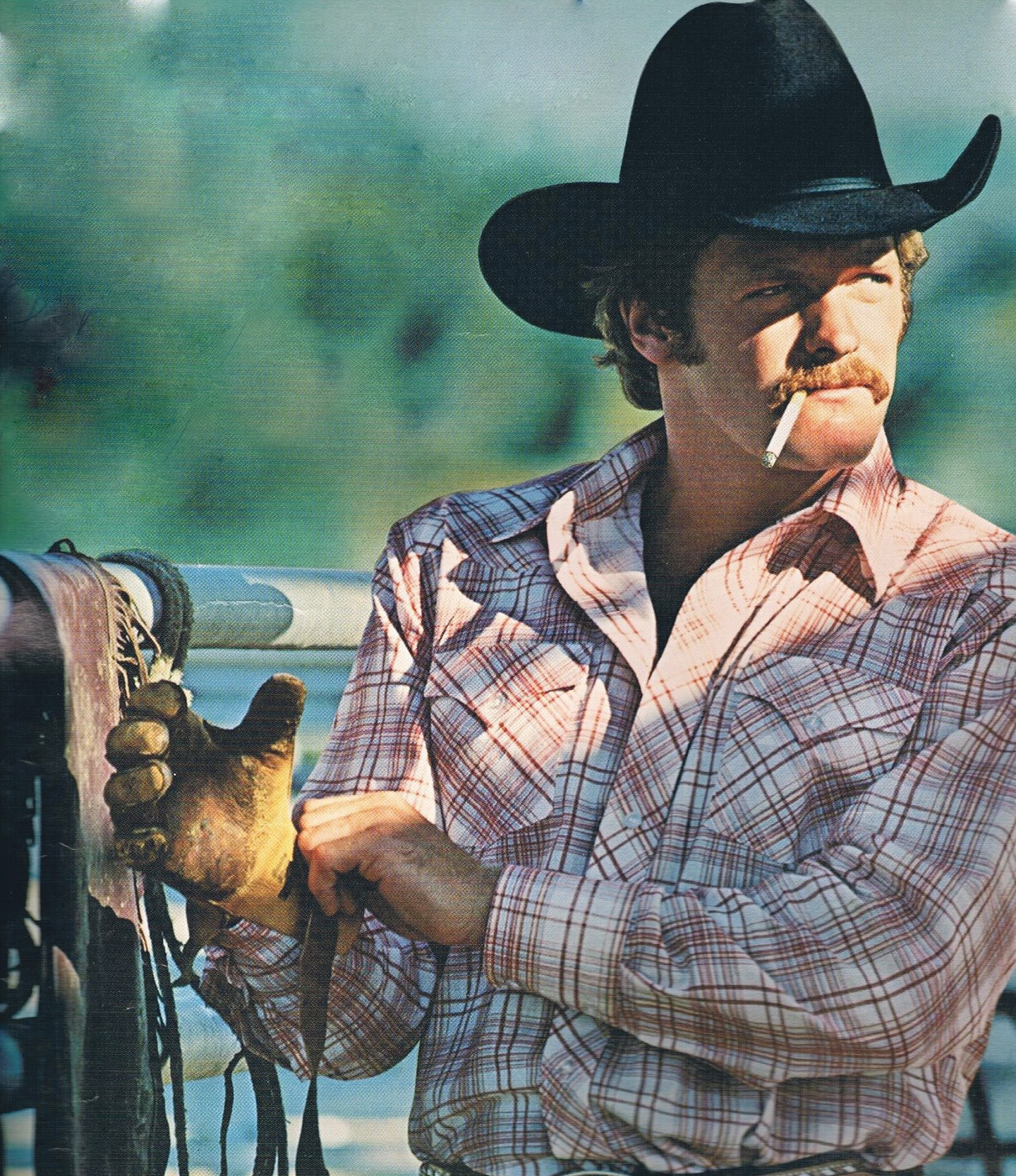

Sander got his first break when he was cast as the Winston Rodeo Cowboy, plying cigarettes in magazine advertisements. With his push-broom mustache and ruggedly handsome looks, marketers needed only to adorn him with a flannel shirt and a cowboy hat. From there, he landed his first commercial spot—an ad for Burger Chef, playing a trucker eating a breakfast sandwich. His line: “Mmmm, ain’t no beatin’ that grease.” That job got him his Screen Actors Guild card, a turning point in his career.

His breakthrough came when, in 1983, he joined The Groundlings Theatre & School in LA, considered one of the nation’s leading improv training programs. There, he met comedians Phil Hartman and Jon Lovitz. Sander’s son and daughter refer to Lovitz as “Uncle Jon,” and Lovitz says Sander is “like a brother” to him. He praises Sander’s versatility and his dedication to the craft: “He never phones in a performance.” He says Sander, like all members of the Groundlings, would rehearse sketches “hundreds” of times to get them right.

“He can do drama, comedy, and character work, and he can use his own personality and just be himself,” Lovitz says. “He’s a big guy with a heart of mush.”

Actor Richard Karn, who played opposite Sander in Home Improvement, calls his friend “a large presence” in the room. “Casey’s strength is his personality,” Karn says. “When a character actor shows up on the set, they have to, without necessarily taking over, create a presence instantly. Character actors have to put their noses to the grindstone.”

Karn and Sander both attended Eckstein Middle School in Seattle, but didn’t know each other because Sander is a year older. On the set, they would rehash their younger years—Karn had also played Little League baseball—and they went on to work on philanthropic projects together. For five years, Karn ran a celebrity golf tournament and Sander a celebrity baseball game, resulting in more than $1 million donated to Seattle’s Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and Overlake Medical Center in Bellevue.

In 1993, Sander got his biggest break: He was cast as Wade Swoboda on the ABC sitcom Grace Under Fire, starring Brett Butler. Swoboda created pottery (as Sander does in real life) and represented a Vietnam War veteran who went on to a successful postwar life. Until then, most Vietnam vets had been portrayed on TV as damaged goods. The show lasted five seasons, and Sander says he received hundreds of letters from vets lauding his performance.

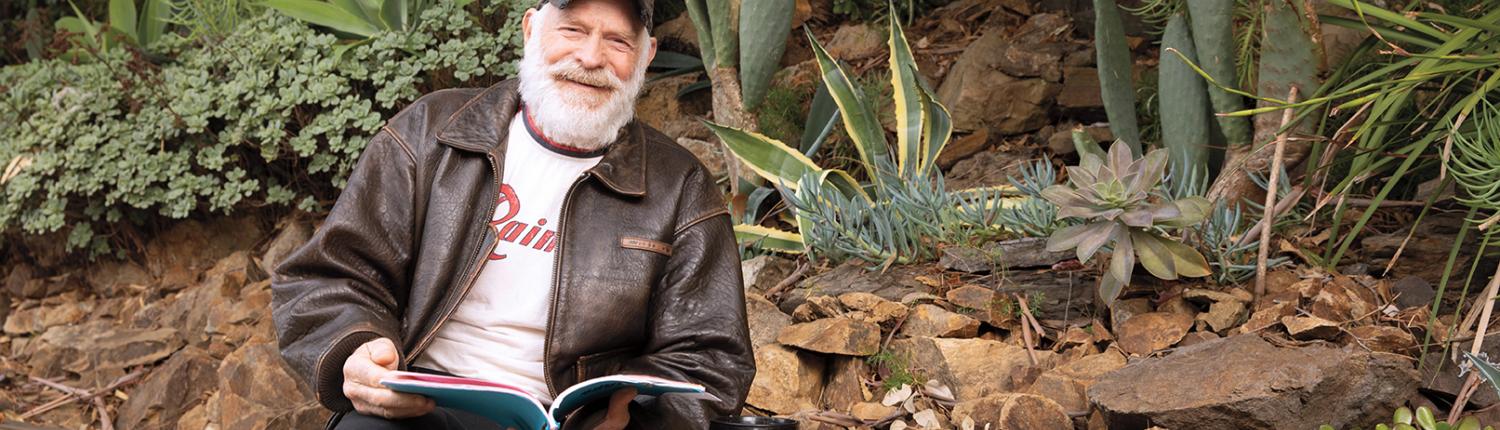

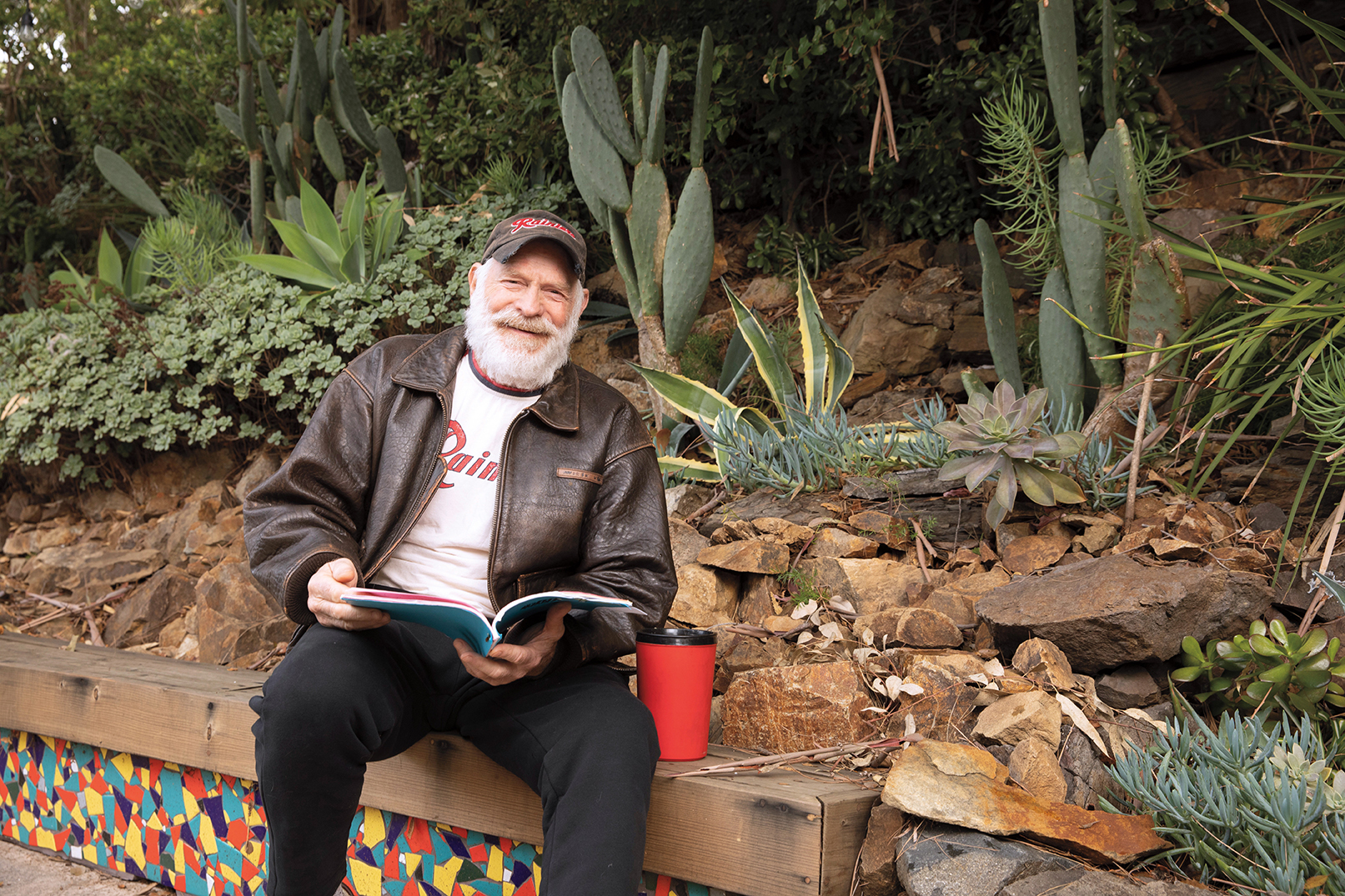

Now 64, Sander sits in his Newbury Park, Calif., backyard, which he’s planted with cactuses and succulents. He dips Copenhagen tobacco, a holdover from his playing days. His eyes are crystalline blue, his figure still ropy with muscle. He is frequently recognized in public, “which I look at as an acknowledgment of good work.” He does regular voiceover work in commercials—he’s been the voice of Goodyear tires for three years—and for video games, including Mafia III and Call of Juarez: The Cartel.

Sander was married at 32 and divorced six years later; he has two grown children, ages 31 and 29. He has spent the last 25 years living in a two-story house in the suburbs. That is by design. “I am a dad first, 100%,” Sander says. “And I wanted to raise my kids outside of LA.”

On a cloudless October day, near where wildfires scorched portions of Newbury Park just days before, Sander reflects on his favorite dramatic role: that of a firefighter struggling to survive third-degree burns on a Season 12 episode of Grey’s Anatomy (“Things We Lost in the Fire,” 2015).

The fictional “Casey” lies on a hospital bed, his breath coming in fitful gasps as tiny, air-exchanging alveoli in his damaged lungs collapse under the weight of the burns.

But it’s more than that. The role is personal: Sander’s father, an Air Force lieutenant colonel who served in World War II, contracted non-smoking-related emphysema—likely from exposure to silica dust during his service in Africa—and was bedridden from the time Sander was 6. He died when his son was 11. The tears on the show weren’t acting.

“This is my dad,” Sander says. “The dad who never saw me play sports, who never played catch with me. I got an understanding of how difficult it must have been for him to talk because I did a lot of those scenes with no air in my lungs.”

But a character actor can dwell on past glories only for so long. A dry-erase calendar on the wall lists Sander’s audition dates. He gets half his work that way; the balance is offered to him. Acting takes hustle. And perspective. Nearby is a collage of photos from family vacations at Sander’s cabin in Port Townsend, Wash., where he likes to chop wood and put his kayak on the Sound, sometimes for as long as 10 hours.

Sander, meantime, is his own worst critic. While some actors never watch their performances, he studies video—not for body language or timing, but for something more ineffable: Could I have approached a character differently, and would that have added to the final product?

Still, he is sanguine, an actor who pursues his craft with the same passion with which he once pursued baseball. He cannot explain life’s twists and turns. Nor does he try. In Hollywood, there is always a second act.